At The Cliff’s Edge

They had nothing to lose. Suspended from school, no one at home, no one who cared anyway; they were looking for trouble just to give the day meaning.Tally, fifteen years old, with dark eyeliner and silver hoop earrings, she was the leader, though this was never said out loud. She just assumed the position.Di, Princess of Death; black hair, black eyes and a black mood that hung over her like a cold front.And Jo, in her ripped jeans and t-shirt with long sleeves that hid the boy’s names she scratched across her arms.She was the only one who dared to say they were going too far but Di and Tally never listened and teased her for being a soft touch.

They had nothing to lose. Suspended from school, no one at home, no one who cared anyway; they were looking for trouble just to give the day meaning.Tally, fifteen years old, with dark eyeliner and silver hoop earrings, she was the leader, though this was never said out loud. She just assumed the position.Di, Princess of Death; black hair, black eyes and a black mood that hung over her like a cold front.And Jo, in her ripped jeans and t-shirt with long sleeves that hid the boy’s names she scratched across her arms.She was the only one who dared to say they were going too far but Di and Tally never listened and teased her for being a soft touch.

In the reserve – bright sky, cool wind, bored shitless – needing money and making plans.

Mums with babies; it was Di’s idea of course.

Di, whose mother left her with the aunt from hell when she was three years old. Mums with prams couldn’t run away and you’d do anything to protect your baby wouldn’t you?

The first time they did it they weren’t sure — what if the mums said piss off and left them with the baby.

What if they didn’t care? But the mums did. It was easy pickings and Di laughed at them when they cried out, my baby, my baby. She spat in the face of one woman who said her mother would be ashamed of what she was doing.

— Fuck off, she dumped the baby back in the stroller.

It was a big haul, sometimes more than fifty dollars, other times ten bucks.

— You cheap slut, Tally said to the mum with $2.60 in her purse.

Tally let Di take the lead for a change. She was fast undoing the safety strap and she held the baby high in the air as if she would drop the little thing at any moment.

Tally collected the money in Jo’s black cap while Jo kept lookout. Left, right, check each way.

They started to get bolshy, sometimes grabbing two babies at once while the pair of mothers howled and emptied their purses.

They stashed away more than $200 and spent at least that much in the main street shops. It felt good to have money and to get it out in front of the pretty girls and boys in Mac’s Milk Bar on a Friday night.

It changed one day. It was a cold morning. The sort of morning where the chill of the air sneaks across your face without you even realising. The reserve was empty except for one woman who sat alone on a bench looking out across the grass. She was watching the way it swayed in the wind as she mouthed a song playing in her head. She turned her face towards the winter sun, tilting her head upwards, just a little, letting the wind play across her cold cheeks. The fresh ocean air breathed itself deep into her body. Jo watched the woman do this, but then it made her look away, like she was seeing something so secret and private that it disturbed her.

— Let’s go into town and get some chips, she said to her friends.

They blanked out her comment and headed towards the bench. The woman stood up, arched her back and ran her hand across her swollen stomach. She leaned into the wind to step forward but Di’s voice stopped her in her tracks.

— We’re gonna kill yer baby.

The woman stared into Di’s black eyes trying to hide the flicker of fear that ran across her face but Di didn’t notice.

— That would be very sad if you did that.

The woman didn’t sound sad. She said it firm. Di took a step forward.

— I’m gonna punch you in the stomach.

The woman stood with both feet an even distance apart, toes turned out.

— I’ve already lost a baby.

Di backed away a little. Then she moved forward again, closer this time. She could have reached out her arm and touched the woman’s stomach, if she wanted to. The woman sat back down on the bench, she didn’t know what else to do. Jo sat next to her on one side and Tally on the other. From a distance, if anyone had been in the park, they would have seen, what looked like a mother with her two daughters or an aunt maybe, out with her nieces, resting and talking on the bench. Jo couldn’t help herself.

— How did your baby die?

The woman told them about the baby who never made it. She told them how small he was and how she held him in the palm of her hand like a small bird. They had a funeral for him, up on the soft edge of the cliff where the rocks cut into the sea without permission.

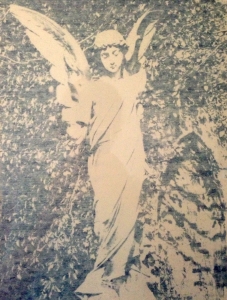

— We call it the Angel Spot.

She talked about her baby and the next child, a girl – and now another on the way. Jo leaned in close.

— Do you want a girl or boy?

The woman didn’t care she told them.

— You don’t mind if the next one is a boy or girl- so long as the baby lives.

Di stood a small distance away, kicking her shoe against a round, grey stone that moved slightly every time she knocked it.

— I reckon push her round, see how fast she can run with that fat belly of hers.

Tally and Jo ignored her, they wanted to know more about this woman’s dead son.

— You don’t think you’ll love your baby even before he’s born. He just stopped breathing you know, no reason, it left a big hole in here.

The woman tapped her fingertips against her chest, just above her heart. The girls looked at the place she had touched- as if they would be able to see something, an image of the lost Angel boy perhaps. The woman watched them looking at her and wondered what they were searching for.

Finally she spoke.

— What school do you go to?

She wanted to get the girls talking, they wouldn’t hurt her if she kept them talking.

— Don’t tell her, Di flung the words across the space between them.

She hovered over the bench, not sitting down, not stopping- but moving and circling the three figures on the park seat,

— Don’t tell her, she’ll dob on you.

Tally glared at her friend.

— Shut up

Di kicked the stone again, it lifted out of the ground this time and paused almost as if it was going to roll away. She bent down and picked it up and felt its cool, stone skin in the curve of her palm.

— We’re suspended, Tally told the woman — for three days.

The woman nodded. She wanted to ask them what they did that got them suspended but she didn’t dare. Instead she said,

— And your mum?

Di dropped the stone from one hand to another; like it was a ball. Jo spoke in a quiet voice,

— My mum’s at work, she doesn’t know I’m off school.

Di wrapped her chubby fingers around the stone and held it fast in her clenched fist.

— Shut up, ya dirty slut, she doesn’t care about ya mum.

Tally said nothing about Di’s attack on Jo. It was one of their unwritten codes, it was what Di did; she slagged off at Jo. And if she didn’t do it to Jo she might turn on Tally. Di was angry at the world and everything in it, they knew that and Jo was simply an easy target. In her defence, Jo pulled her cap down, almost covering her eyes and kicked at the ground, smearing the edges of her sandshoes with the green scars of wet grass.

— I’m bored. Di dropped the stone to the ground. Its fall was soundless.

— Fucken bored.

Tally ignored her friend. She was curious.

— What’s it like to be preggers?

The woman opened her eyes wide, she was surprised by the question, Was it a trick? No, the two girls sitting either side of her wanted to know. She rolled her fingers across her stomach.

— It’s like being a cat, a fat cat.

They laughed. Di turned her back to them.

— And everything seems more . . . she hesitated, — more beautiful, you know, the trees are taller and seem to have more leaves and the grass …the grass looks so green, it’s like I see everything more clearly.

She stopped talking. Had she said too much? She stood up without notice.

— I have to go now.

As she walked away from the three girls, her body tensed fearing a ricochet of rocks from Di. She didn’t look back as she left. She didn’t know if they stayed on the bench talking or if they walked away, back to their empty homes. She had one clear picture in her mind. It was the front door of her own house; the bright, yellow, wooden door that was always open. Come in, welcome, come in, this door picture called to her and helped her find her way home. She pushed the unlocked door open and crumpled onto the living room rug and cried.

She was still crying when her husband came home with their daughter but the day was forgotten when her labour started later that evening. She never called the police, she was too busy birthing her son.

*

Two months later Jo and Tally bumped into the woman at a shoe shop in the main street. They cooed at the baby sleeping in the blue sling close to his mother’s chest.

— Di’s gone, sent to another foster home, another school, they told her

The woman nodded and placed a protective arm across her baby’s back. Jo put her hand on her own tummy and smiled at her. The woman wanted to ask them more – about that day in the park, had they thought about what happened, did it matter? Something in her froze, she had her son close and could feel his gentle baby breaths against her chest – yet she couldn’t move. She stood in the middle of the shop surrounded by shelves brimming with rows of shoes that reached right up to the ceiling.

— See ya.

The girls waved goodbye and disappeared out the door swinging their new trainers in shiny plastic bags. They never saw the woman again. Sometimes they bragged to their school mates about the Angel Spot, they knew where it was.

— We’ll show you for a dollar.

And they took them To the edge of the cliff, where three tall, hoop pines stood in a row and where a woman scattered the ashes of her baby.

*

© Susanna Freymark

First published in Maygog Anthology of Short Stories Volume II,

Maygog Publishing, 2007